University College tries to build a quadrangle

Benefactions, Fund-raising, Civil War and Commonwealth: University College tries to build a quadrangle

Robin Darwall-Smith

After Julian’s talk about the birth of Corpus Christi, I will now tell a story about an existing College which chose to replace all its buildings a couple of centuries after they had been built.

I am taking you to the south side of High Street to University College, known as “Univ.”

Univ today

Robin Darwall-Smith

Those of you who came by coach may recognise it. It is, with Balliol and Merton, one of Oxford’s three thirteenth-century foundations, and each claims to be the oldest College.

In spite of its age, Univ. was a small foundation. By 1500 it comprised seven Fellows, and no undergraduates. We gave preference in electing Fellows to applicants from the dioceses of Durham and York.

As a small foundation, we had a small quadrangle. Here are two images of it.

BODLEIAN - shelfmarks needed

The left one, by John Bereblock, is one of a set of images drawn for Elizabeth I in 1566; the right one, by Anthony Wood, was drawn in about 1668.

As you can see from Wood’s drawing this quad was not the result of one complete plan. The Chapel, here, was finished in 1398; the Hall, along the east side, was finished by about 1450, and the tower built in about 1460.

I now take you forwards to the early 17th century. By now Univ was accepting undergraduate students, and the College’s first undergraduate scholarships had recently been endowed. This quad would by 1600 have been a bit of a squash.

So Univ was in need of a new quadrangle. And the early 17th century was a great age for building in Oxford. Merton added a new quadrangle, Fellows’ Quadrangle, and Jesus College and Wadham College were built.

Jesus and Wadham

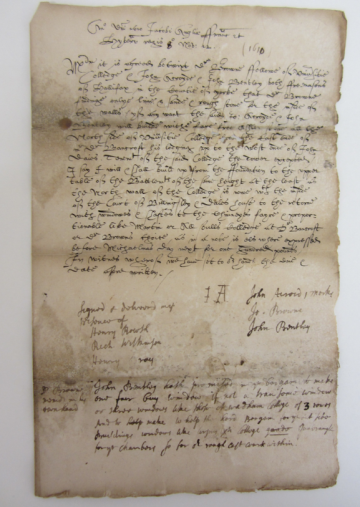

Some wanted Univ. to follow suit. In 1610, our Senior Fellow, John Browne, drew up this contract with two masons working at Merton to work at Univ. He was ambitious, wanting windows“fayre and proportionable like Merton or All Soules Colledge”. Nothing came of this. There weren’t the funds; and Browne himself resigned his Fellowship in 1612, dying the following year.

Matters lay dormant for two decades, but then Univ had two strokes of luck. In 1631, an Old Members called Sir Simon Bennet, died. Here he is:

Sir Simon Bennet

univ?

Bennet was childless, wealthy, and fond of Univ - the ideal benefactor. He was also an intelligent benefactor. He left Univ. some woodland in Northamptonshire called Handley Park, intending that the College cut down the timber, selling it to pay for a new quadrangle, and then turn the deforested area into farmland, to be rented out to endow new Fellowships and Scholarships. This benefaction is so specific that I suspect that Bennet discussed it with the College. As it was, Bennet’s old tutor, Charles Greenwood, himself gave £1500 towards the new project.

Our second piece of luck occurred in 1632, when we elected as Master Thomas Walker. Walker, a former Fellow of St. John’s, had married a niece of the Chancellor of Oxford, William Laud, and Laud had, er, suggested that the College appoint Walker. Luckily Walker was a good Master. He became the great guiding spirit behind our new quadrangle. He was also a meticulous record-keeper, and it’s thanks to him that we know so much about the project.

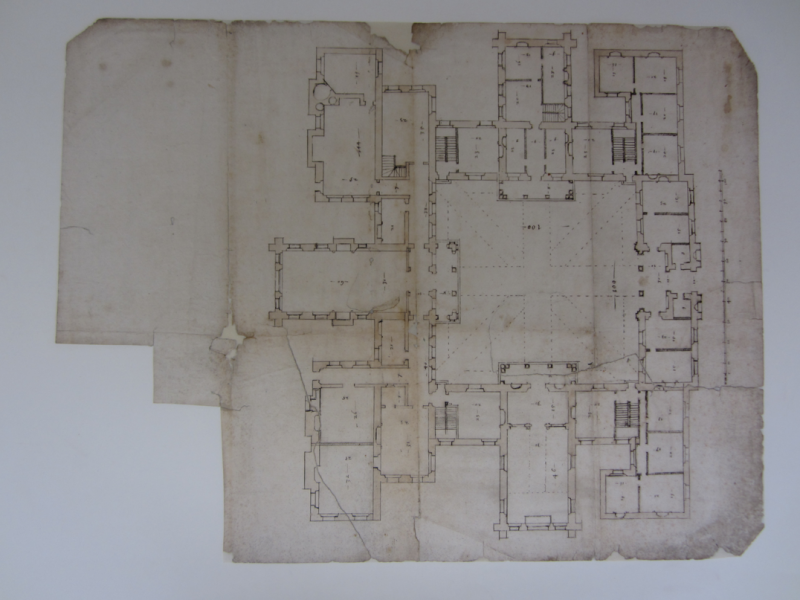

Walker and the Fellows considered at least two proposals for the quad. Here is the first:

Plan for new quad, University College

Univ

Only this plan survives. The High runs along the right-hand edge. You enter the quad, and the Chapel is to your left, and the Hall straight ahead. Elsewhere are sets of rooms.

The late Sir Howard Colvin, whom we’ll meet again later on today, called this proposal“by far the earliest known design for an Oxford or Cambridge College that is consistently classical in style”. And, yes, see those classical porticos inside the quad.

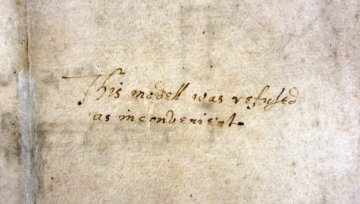

Well, it was daring. But we are dealing with an Oxford College. On the back of this plan, Thomas Walker observed “This modell was refused as inconvenient.”

Annotation by Thomas Walker on the reverse of the plan for the new quad

Univ?

The plan shows what Thomas Walker meant [PICTURE]. Even Colvin admitted:“the plan as a whole is awkward and uneconomical both of space and of building material.” You can see how the attempt to create classical porticoes produces some messy behind-the-scenes moments.

So Thomas Walker and the Fellows looked at the alternative design. Here it is [PICTURE]. Fragments of the original architectural model, still survive, and this is apparently the oldest model of its kind in Britain. It is designed by Richard Maude, who had worked on Canterbury Quad here at St. John’s College - although he had actually parted company with St. John’s in August 1633, apparently in some financial trouble.

Let’s look at Maude’s plan. [PICTURE] Here is the ground floor. The High is on the right hand edge. Three sides of the quad are residential, but facing you as you enter is the south range, with the Chapel to the east, and the Hall to the west. Behind lies a kitchen below and a library above. More traditional - but better designed.

The model shows what Maude intended his quad to look like. So here [PICTURE] is a range as seen from the inside. Here [PICTURE] is one of those ranges as seen from the outside.

Look at those gables, described by Howard Colvin as “mannerist”. Where did they come from? In the interior of Canterbury Quad [PICTURE] we see little resemblance to Univ: the sober sides lack Univ.’s gables, while this splendid central range goes totally in the other direction. But look at a bit of the Quad not generally seen, namely the north range [PICTURE]. Recognise those gables? This is the portion which Maude built, and I suspect that former St. John’s man, Thomas Walker, saw Maude’s work and wanted this for Univ.

Where Maude got his ideas for gables from is another matter; they certainly look Flemish. However, another Oxford quad begun in the 1620s might have given some ideas [PICTURE] This is the exterior of Oriel. And here is the interior [PICTURE]. So the idea of fancy gables for quads was certainly present in the 1630s.

Anyway, back to Univ. The new building would be larger than its predecessor, as it would occupy both the site of the old quad, but also a house to the west. It would have three floors. One first-floor plan suggests for how the rooms would be occupied [PICTURE]. Unfortunately this drawing was once damaged by damp. But you should read “chamber” and “bedroom”.

On 17 April 1634 the foundation stone of the new quadrangle was laid. Work started on the west range, so that none of the old quad need yet be demolished. Thomas Walker kept careful tabs on the sale of timber from our new estate. In May 1634, [PICTURE], we sold 280 trees of which, after Simon Bennet’s widow got her cut, £300 came to us.

Everything got off to a splendid start: the west range was completed in the spring of 1635 [PICTURE]. Next up was the north range of the quad, facing the High Street. This [PICTURE] was finished by the spring of 1637. And here is the outside view to the High [PICTURE].

Next up was the south range, with the Hall and Chapel. But Maude had some trouble here. [PICTURE] The Chapel is to the east, the Hall to the west, and in between the buttery with a passageway to the kitchen. But that bit in between really foxed Maude.

Let’s go in closer [PICTURE]. You can see the entrances to the Hall and the Chapel with the buttery in the middle. You’d enter the Chapel to the left, and the Hall passage to the right. In the passage you turned left into the buttery. These stairs lead to the Library. These steps from the buttery passage led the kitchen. Note that the Chapel here has just four side windows.

But Maude (or Walker) was unhappy with this design, and here is another try [PICTURE]. The two entrances are much closer together. As you aim for the Hall, turn sharp right, to enter the passage there, with the buttery again to your left. And the staircase to the Library has been moved down south. Also, there are more windows in the Chapel, with five on this side alone.

You may have spotted something in the left-hand corner. Here’s the whole drawing [PICTURE]. Maude and Walker were now planning to insert a little cloister by the Chapel.

Meanwhile, the College was having trouble with Sir Simon Bennet’s family. His widow died in 1636, and Handley Park should have come to us. Bennet’s heir was a young nephew, whose guardians refused to hand the property over, and so we had to take them to court. It wasn’t until November 1639 that we took delivery of the property.

And so we could think about the Chapel. The 1630s was the heyday of “Arminianism”, that branch of Anglicanism exemplified by William Laud. Arminians like Thomas Walker, William Laud’s nephew in law, believed that God should be worshipped in magnificent surroundings. When Walker planned his Chapel, he sought out the best glass painter for its windows.

This was Abraham van Linge, a Dutchman who with his brother Bernard had already worked in several Colleges, including Wadham, Lincoln, Queen’s, and Christ Church.

Van Linge, as well as being a considerable artist, had a considerable artistic temperament. A letter at Magdalen College says of him ‘This duch is a slye fellowe and stronge headed and must have a Ruffe muzell or els there is no doinge with him’.

Magdalen never employed van Linge, but Univ was prepared to “do with” him. We commissioned eight side windows and an east window, paying him £190 between August 1641 and May 1642, with an extra £100 to follow when the east window was complete. Here [PICTURE] is a receipt signed by van Linge.

But there are hints here that all is not well. There are qualifications, such as “if the College doth not goe forward with their worke according to their former agreement”, or, if van Linge “leave the kingdome or otherwise before Easter next.”

The 1630s had been a good period for Oxford. We enjoyed royal support, and most Colleges shared William Laud’s religious beliefs. But by 1641, Charles I and the Long Parliament were at loggerheads, and William Laud had been imprisoned by Parliamentary order the previous year.

By the late summer of 1642 war appeared unavoidable. We see the results in our Buttery Book for 1642/3, which records the expenditure of College members. Early in September, every member of Univ who could fled. A few weeks later some Parliamentarian soldiers briefly occupied Oxford. In the week of 7 October someone wrote in the Book [PICTURE]. “Billet our tenne men or else”. A solider’s threat or a joke? Oxford was at war.

Let’s see where Univ’s great building project stood in autumn 1642. From the High everything looked fine [PICTURE]. Inside, the west range was complete. But the Chapel and Hall were bare walls. There was no cloister; nor would there ever be. And in front of the south range was [PICTURE] the old medieval quadrangle. So the Civil War left Univ stranded between two fragmentary quadrangles.

As for Abraham van Linge, he had completed the eight side windows, but he never completed the east one. He disappears from history: no one knows what happened to him.

I will not tell the tale of Oxford during the Civil War. Let’s move to 1648. The Royalists had lost, and a group of Parliamentary Visitors were purging Oxford of unsound elements. In terms of unsoundness, Univ, led by the nephew in law of the hated Laud, was high up the list. In July 1648, Walker was expelled, as were many Fellows, to be replaced by men chosen by the Visitors.

The new Master, Joshua Hoyle, inherited a grim situation. Univ’s finances were in a mess, and matters reached a climax when in 1654 the Visitors decreed that some of our Fellows could not be paid for three and a half years.

What of our quad? In February 1642, Thomas Walker calculated that the new quadrangle had so far cost almost £5,500 of which all but £1,800 had come from Handley Park. But by the 1650s the Handley Park timber had all been felled. A pause fell on proceedings. But we hoped for better times. This [PICTURE] comes from the College’s accounts of 1651/2. 2 shillings is spent “for a new lock to lock up the new Chappell glasse in the Storehouse”. Those are van Linge’s windows, not yet installed. In addition Richard Maude was long dead: his will dates from 1643.

In December 1655, the College decided to revive the project. A new Master, Francis Johnson, a chaplain of Oliver Cromwell, and the Fellows decided to finish the Hall. They appointed a Fellow, William Offley, to raise funds. They drew up this document [PICTURE], bearing the College seal, to give him authority to receive money on their behalf.

But where would the money come from? Johnson himself and other Fellows chipped in. But William Offley had a difficult job. Most Old Members were Royalists. They would not support a Master and Fellows whom they regarded as usurpers. Only four Old Members and one former Fellow contributed. Instead, Offley looked to other Colleges and to Oxford tradesmen; he even got £10 from the scientist Robert Boyle, then renting a house next door to us [PICTURE]

In the end William Offley raised £450 for the roof. He’d worked hard. The £5500 spent on the first phase of building came largely from the gifts of Simon Bennet and Charles Greenwood. Offley’s £450 came from almost sixty benefactors. And here is the splendid hammerbeam roof [PICTURE]. Offley did a good job.

At some point, we completed the Hall passage. It was straightened out by Gilbert Scott in the 1850s, but Maude’s revised plan was used Here [PICTURE] is what Maude planned. And here [PICTURE] is William Williams’s engraving of Univ. from 1730.

No further work was done on the quadrangle in the 1650s, and in 1660 Univ underwent fresh change. At the restoration of Charles II, there was another visitation of Oxford, and the Heads of Colleges and Fellows who been ejected in 1648 and were willing and able to return did so. Including Thomas Walker. [PICTURE], as he himself notes in this account book.

Thomas Walker, now in his late sixties, found that the buildings of Univ., apart from the Hall, did not look very different in 1660 from how they had looked in 1648, with two fragmentary quads, an unroofed Chapel, and Abraham van Linge’s windows in storage. Walker decided to complete the Chapel, although, just like William Offley, he had to accept that there were no more grand individual gifts.

But Univ’s Old Members were more willing to help their “real” Master. Of the eleven major donors towards the Chapel, eight had had links with the College.

At last we brought Abraham van Linge’s windows out of storage. Having heard so much about them, you might like to see them. Now it is time. Here is Maude’s final version of the Chapel, to help orientate ourselves [PICTURE]. Maude planned for three windows in the Antechapel, two facing you as you walked in, and one to your left, and then five windows in the Chapel proper.

Van Linge had clearly been briefed on the subject matter. When one entered the Chapel, there were these two windows side by side [PICTURE]. These are the only New Testament scenes. On the left is Christ in the house of Mary and Martha, with Mary listening to his teaching, and Martha grumbling at all the cooking she’s got to do. To the right is Christ expelling the moneychangers from the Temple. These scenes encourage one to be in the right frame of mind to enter the Chapel. The coats of arms are of College benefactors.

The other antechapel window [PICTURE] shows a scene from Genesis. Here is Jacob asleep, dreaming of the ladder bringing angels up and down from heaven. This again has a preparatory feeling to it; of being ready to climb the ladder to heaven.

Now we enter the Chapel proper. There are three windows on the south side, and here are the two nearest the altar [PICTURE]. To the left are Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden, with the serpent. Several windows reflect on obedience and disobedience, and Adam and Eve are being disobedient. Also, like other widows, it shows different parts of the same story, so here are Adam and Eve expelled from the Garden of Eden.

In the next window, we see a glum Adam and Eve taking a breather from their life of toil. But in the background is a scene from another story: Abraham entertaining angels.

This links to the third picture on the south side of the Chapel [PICTURE]. Here is Abraham, obedient to God, about to sacrifice his son Isaac, and prevented by an angel. The New Testament centres on a father sacrificing his son. This is the second theme of the windows, namely prefigurations of the New Testament from the Old.

Time for the two last windows, on the north side of the Chapel. [PICTURE] To the left is Elijah carried up to heaven as prefiguring the Ascension. To the right is Jonah and the Whale. In the background Jonah is thrown overboard to a hungry whale, and in the foreground he’s spewed out having spent three days there. And Christ spent three days in the tomb before his Resurrection.

Nicolaus Pevsner thought the Univ. windows van Linge’s masterpiece. I won’t disagree.

But there was no east window. So Univ Chapel just had clear glass in its east window when, on 20 March 1666 it was consecrated. Sadly, the person above all who should have been present was not. Thomas Walker had died on 6 December 1665.

A former Fellow, Richard Clayton, became Master, but another Fellow, Obadiah Walker (no relation to Thomas), was the driving force in College for the next two decades.

The west, north and south ranges were finished. Now it was time for the south wing. Just to remind you, here it is [PICTURE], with the Chapel here and Hall here.

At Univ, as elsewhere, Gentleman Commoners had usually given plate to the College. From April 1669, our Gentleman Commoners gave money towards the building project instead. We also borrowed at least £800 between 1661 and 1682.

The kitchen and library wing seems to have cost just under £400, and we raised £252 from 26 people. The Library seems to have been ready by 1672, and we have this fine drawing of it from 1674 [PICTURE]. Alas it was gutted by the Victorians when the current Library was built.

Only the east range remained. Some of the old quad was still standing. The accounts of 1671/2 record work carried out on the roofs of the old and new buildings [PICTURE].

We turned once again to our Old Members. We have examples of letters sent to them soliciting money, including this one [PICTURE]. Here are extracts from it:

“Your aged Mother, and not yours alone, but of this whole University ... craves your assistance in the time of her necessity ... there remains a great part of the fourth side of the Quadrangle unfinished. ... we have very great hopes that you will not be wanting to us in this our necessity.”

The language is of the seventeenth century, but many of you must have received brochures with similar arguments. Obadiah Walker and his team, though, had to write every letter themselves. In the accounts for 1675/6. [PICTURE], we bought “gilt paper for our Letters to Benefactors”.

Well, we raised over £400. Humphrey Prideaux, a Student at Christ Church, wrote to a colleague in April 1675 that Univ. had just started the east side of its quad ‘which will make that colledge looke very handsom, and not inferior in beuty to any other in the University’, and, in August 1676, wrote that ‘University Coll: is now all built up’.

Well, you can decide whether to agree with Prideaux. For in 1675, just as the east range was being built, David Loggan, for his Oxoniana Illustrata, included this engraving of the completed quadrangle [PICTURE]. I think it looks pretty good.

And so, forty years on, at last Univ’s quadrangle was completed. It had been hard work. And not cheap. Calculating the quad’s building costs is are not easy, but I think it was about £8000. This compares with Wadham College, which cost £11,000 while Canterbury Quad in St. John’s, which covered only three sides, cost over £5,500.

I am at the end of my slot, so it is time to stop. The Quad has undergone several changes: the Antechapel was halved in the 1690s; the Hall got a Gothic ceiling in the 1760s, removed in 1904; the Chapel got a new east window in the 1860s. But that’s another story.

But did Univ. influence any other Colleges? Funnily enough, yes. This is the Second Quadrangle of Jesus College.

In 1639 Jesus College began a second quadrangle, and they employed - Richard Maude. They must have liked his design for Univ. And, if you thought that the construction of the Main Quad of Univ. was a protracted affair, Jesus’s Second Quad wasn’t finished until the early 18th century. But that is, again, another story.