Christ Church ups its game

Christ Church ups its game: The 'Great Rebuilding' - Christ Church's eighteenth-century Renaissance

Judith Curthoys

It is hard to believe that Christ Church – never a shrinking violet on the collegiate scene - ever felt the need to ‘up its game’! Right from the start, its scale was immense and its style impressive.

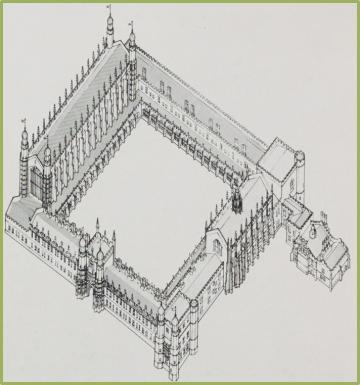

Proposed buildings for Cardinal College, drawn by Daphne Hart for Howard Colvin's Unbuilt Oxford

Permission?

In 1525, when it was first founded as Cardinal College, by Thomas Wolsey, his scheme was for buildings and a community unsurpassed in Oxford or, even, Cambridge. The dining hall was to match that of Hampton Court; its chapel was designed to just pip that of King’s College in length; and its quadrangle is nearly 250’ square. Thomas Cromwell, in charge of the project, said that "..the like was never seen for largeness, beauty, sumptuous, curious and substantial building." But Wolsey never had the chance to complete his scheme. He fell from grace in 1529 and, while building work continued into 1530, the grand design was rolled up and tucked away in a corner of the mason’s office never to be seen again.

Agas

Henry VIII refounded the college in 1546 as the unique college-cum-cathedral that it is today, but the place remained a building site for many years, muddy and unloved, and very inconvenient with its mixture of old monastic premises, a dilapidated medieval inn, a partly-demolished chapel - now the cathedral for the newly-created diocese of Oxford - and Wolsey’s incomplete structures. Only the dining hall, the kitchen, and some of the senior members’ lodgings had been finished before Wolsey’s fall.

Over the next century, schemes were considered, and some buildings were beautified, including the stairs above the stairs to the Hall in the 1640s,

Hall stairs vault

but events always seemed to get in the way of any major work. Not least the Civil War, when the foundations of Wolsey’s partially-built chapel were dug out to provide building materials for the city’s defences. It was not until the 1660s, with the Restoration and the installation of John Fell as dean that any new building was seriously considered. Fell was responsible for the final closing of the quad, the building of a new residential block, and the construction - with Christopher Wren - of the iconic Tom Tower.

Loggan

At the beginning of the eighteenth century, Fell’s impetus was continued by the energetic polymath Henry Aldrich. After a mere twenty years of peace without the sound of building and builders, attention was turned to accommodation for more junior, but far more wealthy, members.

Peckwater Quad – Loggan close-up

The medieval Peckwater Inn had been acquired by Wolsey as part of the site for Cardinal College.[1] Initially used to house Wolsey’s workmen and their workshops, the Inn soon became an annexe for members whose numbers were rising rapidly. In the early seventeenth century, the medieval building was soon under scaffolding being revamped at lightning speed in a Jacobethan style.

Within a century, this homely appearance had fallen out of favour. Oxford was considered a “Gothic backwater”, but some colleges - like the Queen's and Trinity, and the University itself – were beginning to adopt a classical style. Aldrich, inspired by Palladio, and influential in this rebuilding across Oxford, wanted to make his mark on his own college, to make it grander, more stylish, and to encourage the wealthy through the gates.[2]

Aldrich

In 1706, Christ Church received a bequest of nearly £3000 and Aldrich seized upon it.[3] Three foundation stones were laid in Peckwater on Saturday 26 January 1706.[4] All of the Chapter, and the noblemen in residence at the time, each added a stone to get the building off to a fine start.[5] Over the next four years, the domestic Tudor quad was turned into a grand edifice - "a serious and academic essay in classicism".

Peck now

Peckwater was ahead of its time in its stern and strictly classical use of the Ionic ordere. The new stately homes of Castle Howard and Blenheim Palace were more Baroque.[6] Each wing is identical, and gives the appearance of an Italian palazzo. The ground floor is rusticated; then the piano nobile and the second floor have rounded pilasters on the central five bays underneath a grand pediment, and square pilasters for the five bays either side. A balustrade hides the low roof and the cocklofts.[7] Aldrich’s design is a peculiarly English adaption of Palladianism adopted by connoisseurs such as Inigo Jones, something very definitely Italian but “distinctly English”.[8]

Most rooms were rather grand. On the first floor were – in fact, still are - large double sets for gentlemen. In the attics were more fundamental rooms for servants or for servitors.[9]

Aldrich did not see Peckwater completed. William Townesend, the mason, had completed all his tasks, but it is unlikely that the expensive wainscotting was finally nailed in before Aldrich’s death at the end of 1710. Internal finishes were the responsibility of the residents of the rooms. This was funded by the ‘thirds’ system: the first resident of the room suffered the full cost but was reimbursed a third by his successor in the room. In turn, his successor paid a third and so on, until the figure reached just £5 when it was written off.[10]

South prospect

Peckwater Quad was the first outward demonstration of Christ Church’s increasing grandeur. Another great project with which Aldrich has been credited, although he did not live to see this one even begun, was the new library which completed the quad. Aldrich had certainly planned a new building here, probably another residential wing on a grand scale, this time using a monumental Corinthian with a subordinate Doric orders.[11] The temple of Bacchus at Baalbek is said to have been an influence on the dean but there were many more such as the Temple of Hadrian in Rome, Chatsworth in Derbyshire, and the portico at Old St Paul’s.[12]

Judging by the ground floor plan, Aldrich’s building would have had nine bays with an open, central entrance. Two staircases against the south walls would have risen at the east and west ends. The rooms would have been generous, designed for the noblemen that Christ Church wished to attract. Aldrich’s designs reflected status. The more composed and restrained Peckwater buildings were better suited to the gentlemen commoners.[13] It was not until 1716 that another bequest allowed building to begin. Work was to follow Aldrich’s design for the exterior, but the interior would now be “the finest library that belongs to any society in Europe”.[14]

A new library had become an essential, rather than a solely desirable, addition to Christ Church’s buildings. The old library, while still magnificent, was a bit dilapidated and furnished with old-fashioned presses and cupboards that were bursting at the seams.

The New Library was planned, not just as a repository for books but, like Peckwater, as a means to encourage wealthy aristocrats to Christ Church. There may well have been an element of competition, too; other colleges in Cambridge, Dublin, and Oxford were planning or had recently begun new and magnificent libraries. Under the supervisory eye of George Clarke, successor to Aldrich in his influence on Oxford architecture and who had collaborated with Nicholas Hawksmoor and William Townesend, whose skills were employed on numerous buildings around Oxford including All Saints’ church, and the cloister and Fellows’ Building at Corpus Christi College, the building began.[15]

Townesend sketches.

The bold design was a deliberate contrast with the severity of Peckwater, this time based on Michelangelo’s Capitoline palaces, and imitating the Wren Library at Trinity College, Cambridge, and St Mark’s Library in Venice.[16] The ground floor would be a loggia, open to the elements on three sides, and the upper floor would house the library.[17] The façade would be a giant order rather than the purer Doric and Ionic orders of Trinity’s. The beautiful stone staircase was à la mode, reflecting the growing fashion for stone staircases with iron balustrades and mahogany handrails.[18]

Staircase

Construction was funded by gifts from old members. It was a long, slow process - members had, after all, only just been asked to contribute to the re-building of Peckwater Quad. There were years when no money came in at all.[19] Dean Boulter even bought a couple of lottery tickets, but he was not on a winning streak.[20]

By Townesend’s death in 1739, most of the shell was complete. After September 1742, by which time the roof had been leaded and the windows sashed and glazed, work ground to a halt with only £1 17s 3d left in the kitty. Four years went by before the coffers were sufficiently replenished to allow the college carpenters to begin on the timber work.

But, long before this, the original designs for the interior of the Upper Library were thrown into confusion. The upper room is 142' long, 30' wide, and 37' high, and the original plan was to have shelves at right angles to the long walls, much as they were in medieval libraries and in the more contemporary library at the Queen’s College. But huge gifts of books had continued to arrive: Lewis Atterbury, the dean’s brother, had given 3000 pamphlets in 1722; Canon William Stratford bequeathed 5000 books in 1729; and, in 1731, not only 2,500 books, but all the scientific instruments belonging to Charles Boyle, the fourth earl of Orrery, were given to Christ Church.[21] In 1737, the enormous bequest of the archbishop of Canterbury, William Wake, was delivered.[22] Space had to be found for all of these, along with Aldrich’s collection of books and music, which had already caused a major upheaval in the old library.

Shelving design

These huge bequests prompted a re-think; the shelves were now to be placed against the walls, rather than at right-angles; in consequence, four of the seven windows were blocked up on the inside. This seems an odd thing to do, and it has been suggested that this provided additional space for the new books. This seems unlikely and a second idea is that the new bequests were so grand, and with so many artefacts as well as volumes, that the medieval shelving style was abandoned to create a space for display and to turn the library into more of a ‘cabinet of curiosities’.[23]

Interior of the Upper Library

Funds for the decoration of the Upper Library were pulled in by David Gregory, first treasurer and then dean, and the work was done by two London carpenters, George Shakespeare and John Phillips, who worked with Norwegian oak to produce the pedimented bookcases and the gallery. A local craftsman, Thomas Roberts, who beautified the Senior Common Room at St John's College and the Radcliffe Camera, was responsible for the elaborate plasterwork, including the staircase ceiling, the decoration under the gallery, and the remarkable ‘trophies’ - the drops of scientific and musical instruments, celebrating and complementing the collections of music and Orrery’s scientific and astronomical instruments.[24]

Plasterwork

The design was of Rococo exuberance, with overtones of Grinling Gibbons, in sharp contrast to the restrained classical exterior.[25] In 1762 and 1763, the finishing touches were added: the engraving of the Christ Church arms for bookplates had been commissioned, and inkstands purchased ready to stand on the five new mahogany desks. Thomas Chippendale’s stools and George James's matching steps had been brought from London, matting had been laid, locks were installed, the painter had finished, and the mahogany rail on the stairs had been fitted.[26] The statue of John Locke by Rysbrack was already standing on the library stairs.[27] And finally the whole library was cleaned and dusted ready to receive the books.[28]

But, yet again, events prompted another re-design. General Sir John Guise, who had left Christ Church in 1702 and become a professional soldier serving with Marlborough, was an avid acquirer of Renaissance art. Just as the library project was nearing completion, his extraordinary collection, consisting of 258 pictures and over 900 drawings, was given to Christ Church.[29]

Example of Guise collection

A brave decision was made to close in the fashionable open loggia and create a gallery, and it was Henry Keene, surveyor to the Dean and Chapter of Westminster Abbey, who was given the challenge.[30] Keene was a Gothic revivalist, influenced by the architecture of the abbey, but most of Keene's works in Oxford were classical in style.[31] At Christ Church he had little choice in his adaptation of the library.

All of a sudden there was upheaval. The archways leading into the loggia had to be converted into windows and doors; floorboards had to be laid where there would have been stone flags; plasterers and glaziers had to be called back.[32] The lower library was far more restrained in its decoration than the Upper. Bookcases, decorated with simple Greek designs, were placed around parts of the walls with space left for the pictures. The ceilings were the embodiment of simplicity compared with that on the upper floor.

Lower library - west

The ground plan of the whole of Christ Church as the library was going up was recorded by William Williams in the early 1730s, as one of a series illustrating the Oxford colleges.

Williams’ plan

The plan shows what remained of the old Canterbury College, which was the next project in the great rebuilding of Christ Church. Soon after the library was completed, attention was turned to this medieval survivor.

Demolition sketch by Malchair.

The west side of Canterbury College was lost in the early eighteenth century, under the east end of the New Library. But the complete rebuilding, to bring Canterbury Quad to the same level of grandeur as Peckwater and the Library, was begun in 1773 thanks to a gift of £1000 from Richard Robinson, the archbishop of Armagh, who had been an undergraduate at Christ Church from 1726. The architect chosen by the Chapter was James Wyatt. Wyatt, whose buildings combined refined decoration with new constructional techniques, exactly in accord with the industrial and aesthetic mood of the time, had designed the Radcliffe Observatory in 1772 which had marked the beginning of nearly forty years predominance over Oxford's architecture.[33]

Two years later, Robinson gave another £1000; both gifts funding the construction of most of the north and part of the south sides.[34] Much of this work was completed by 1775.[35] The design of most of the small quadrangle is simply elegant, designed almost to frame the grand library occupying its west side.[36]

The old gate into Oriel Square, illustrated by Malchair, was not replaced by the magnificent triumphal arch, in uncompromising Doric, until 1778.

Canterbury Gate

It is, possibly, too grand for its location, described by one modern critic as a 'pompous absurdity'.[37] Its southern end - even in the eighteenth century – was tucked away behind Corpus Christi, now ignominiously in that college's car park. Its design was, however, a first; fluted baseless Doric columns had been used for interiors, but not on the outside in England before this.[38] The gate was one of the last classical constructions in Oxford before the revival of Gothicism.

Staircase 4

Canterbury's south-west corner, which matches Peckwater exactly in its exterior design, was not begun until early in 1783. There must have been great excitement on 31 March 1783 when a skeleton “of very large dimensions,” wearing boots and buried with coins of Edward I was uncovered during the digging for the foundations of the south side.[39] This corner alone cost £4000, funded entirely by the munificent archbishop, on the condition that it was used only by undergraduates of the highest social standing.[40]

Peckwater and Canterbury Quadrangles were now grand enough to attract young men from wealthy and influential circles, and the New Library was a major boost to Christ Church's academic facilities, but there was another attraction for those with enquiring minds. As the Library was finished, so the construction of the Anatomy School in 1766/7 put Christ Church head-and-shoulders above other colleges in its science teaching.

Anatomy School engraving

Dean David Gregory had drastically overhauled the curriculum in mathematics and science, and had received a bequest of £1,000 for the creation of the school and the foundation of a readership in anatomy.[41] This gift alone was insufficient, but it was supplemented by Matthew Lee, a graduate in medicine who became a royal physician, and who, in his will, left over £20,000 specifically for the advancement of Westminster Students, and to assist with the construction of the School.[42] Public human dissections were to take place twice a year, for which most spectators had to pay a fee.[43] The project was supervised by the dean, and a decision was soon made to put this new detached building in School Yard, just to the south of the Great Quadrangle, near the kitchen.[44] It is a simple, astylar – almost scientific - box with unembellished sash windows, and plain parapet. Only the staircase to the ‘ground’ floor has any decoration in the form of a small portico.

Plan of theatre

The school rapidly became known as ‘skeleton corner’, with cadavers from the prison used for anatomy teaching. The Oxford Journal of 24 July 1790 records that 'In the afternoon of Monday the bodies [of Shury and Castle, executed for murder] were conveyed in a cart to the Anatomy School at Christ Church, where Dr Thomson, the Reader in Anatomy, next day gave a publick lecture on the two bodies…' A plan of about 1840 shows the school with its tiered seating around a central arena, and a gallery for more spectators.[45]

In the century between 1700 and 1800, Christ Church underwent huge changes. It had long been sumptuous and enormous but it now it was gentrified to a whole new level. It was the beginning of the era of aristocratic Christ Church but also the era of its dominance as a place of academic excellence. It had “upped its game” in every way.

[taken from The Stones of Christ Church (2017)]

[1] Salter, i (1960), 221 & 260. Recent archaeological excavations (2006) have shown the western wall of Peckwater Inn against the cobbled street that continued the present Alfred Street further south into the Great Quadrangle – Chadwick et al (2013); and see Chapter 1.

[2] Hiscock (1960), 15-31; Brittain [2012], 10; Colvin (1983), 9. Hiscock also credits Aldrich with influence, at the very least, in the design for the Old Ashmolean and renovations to St Mary’s church. Dean Henry Aldrich was a real polymath. He was particularly fond of music, and left Christ Church one of the greatest collections of early church and popular scores in the country. But Aldrich was also a talented architect – arguably the equal of Wren, definitely friend and colleague of Gorge Clark at All Souls – who influenced many of the buildings that were springing up in Oxford at the end of the seventeenth and beginning of the eighteenth centuries, including All Saints church and, possibly, the Fellows Building at Corpus Christi College which bears a remarkable resemblance to Peckwater Quad.

[3] Tyack, Oxford: an architectural guide, (1998), 142-143; Thompson, 116; CCA xxxiii.b.15; Bill, ‘The rebuilding of Peckwater Quadrangle at Christ Church’, (unpublished paper) in MR iii.c.1/1/8. Radcliffe’s will was proved on 3 November 1706; Brittain [2012].

[4] The stone laid by Salisbury is said to have described Aldrich as the architect of the quadrangle - Colvin, HUO, v, (1986), 832. The location of the foundation stones is unknown; they were already lost by 1900 (Thompson (1900), 117).

[5] MS Rawl. Letters 37, 75, cited in Bill, ‘The rebuilding....’

[6] Colvin, HUO, v, (1986), 832. The design anticipated developments like Queen's Square in Bath which, too, bears a distinct resemblance to the new quad - Thurley (2013), 297 & 310

[7] Tyack (1998), 142-143

[8] Brittain [2012], 1

[9] Servants of noblemen and ‘privileged Scholars’ were not permitted to lodge in college after 20 May 1773. CCA D&C i.b.6, 243; CCA xxxiii.c.1

[10] CCA D&C i.b.4. Later, rules were laid down about meeting the costs of new sashes and any breakages of windows, following an outbreak of undergraduate vandalism in 1771 when a notice had to be placed in Hall warning of punishment and stigmatisation of anyone found to be breaking windows or lamps - D&C i.b.6, 216 & 197

[11] Colvin (1983), 26; Weeks (2005), 107-138; Colvin, HUO, v (1986), 832. This fourth side had to be separate from the other three in order to maintain a clear route through to Merton Street.

[12] Summerson (1993), 290; Weeks (2005), 110-111

[13] Weeks (2005), 115

[14] HMC, Portland, iii, 217. In between the completion of Peckwater Quad and the commencement of work on the New Library, Townesend was kept busy on other projects around Christ Church, including the repair of the Hall roof in 1720, and on the repair and construction of chimneys and fireplaces - Bod MS Don.c.209. Robert South came up to Christ Church from Westminster School in 1651. A Royalist, South eventually gained a canonry in 1670. He was one of Christ Church’s greatest benefactors, leaving the college his estates in Caversham and Kentish Town.

[15] Cook & Mason (1988), 3; ODNB; Colvin (1995). The contract was signed on 10 January 1717. Other projects included the Front Quad of Queen’s College, the Clarendon Building, the Robinson Building at Oriel College. Townesend also had a hand in the construction of Shotover House, and worked at Blenheim Palace. Hiscock, 38-62; ODNB; Colvin, HUO, v (1986), 830ff

[16] Colvin, HUO, v (1986), 840; McKitterick (1995), 35

[17] Both the Queen’s College library and the Radcliffe Camera in Oxford were designed with open spaces beneath. It was practical, protecting the precious books from damp and rats.

[18] Campbell et al (2014), 99-102. The use of iron balustrades on stone staircases was for practical reasons; an iron balustrade could be fixed using molten lead, impossible on a wooden staircase, and was lighter than stone.

[19] Cook & Mason (1988), 4. John Mason compares this with the funding for All Souls' library which began with a lump sum of £12,000 from Christopher Codrington.

[20] Hiscock (1946) 53; CCL MS 373: CCL MS 373 Library Building Accounts, f.10v

[21] CCA MS Estates 127, f.1; D&C i.b.5, 132; D&C ii.b.1; Chichester, 12

[22] Another 5,000 volumes, plus manuscripts and Wake's coin collection

[23] Weeks (2005), 129; Hiscock (1946), 69

[24] Eric Halfpenny, ‘The Christ Church trophies’, in Galpin Society Journal, xxviii (1975) [on the musical instruments]; CCA D&C i.b.6, 104, 193 & 242.

[25] Tyack (1998), 179-181

[26] Painting was done by the Green family whose business was on the High Street. The iron balustrade was manufactured by Nathan Cooper for which he was paid £90. Cooper also made sconces for the cathedral in 1765.

[27] CCA D&C i.b.6, 8. The statue of a rather gaunt Locke, given by William Lock (probably a relative), was placed in the library in 1754. Although, appropriately, a bust of Aldrich now stands in the opposite niche, in 1946 the space was occupied by the ample Proserpine – Hiscock (1946), 103

[28] CCL MS 373 Library Building Accounts, ff.23-8

[29] CCA MS Estates 127, ff.17-52

[30] Tyack (1998), 181

[31] ODNB. The employment of Keene marked a move towards professional architects from the gentleman-amateur. He and James Wyatt dominated the second half of the eighteenth century - Colvin, HUO, v (1986), 848.

[32] CCA MS Estates 127, ff.28-58. Guise’s collection was sent from John Prestage’s warehouse in London on 17 March 1767 and, presumably, stored in crates until such time as the space was ready. The first catalogue of Christ Church's pictures was printed in 1776 at a cost of £1 17s.

[33] Tyack (1990), 184; Colvin (1986), 850; Greenwold [forthcoming]; Robinson (2012), 195

[34] CCA DP ix.b.1, 80 & 82; D&C i.b.6, 280

[35] Bod MS Top.Oxon.d.247, f.40v

[36] Robinson (2012), 196

[37] Greening Lamborn (1912), 80

[38] Robinson (2012), 197

[39] Bod MS.Top.Oxon. d. 247, f.54v - the remains were collected and re-buried in the cathedral.

[40] Thompson, 165-166; CCA xxiii.b.3; MS Estates 144, f.24; D&C i.b.7, 451 & 454

[41] ODNB; CCA D&C i.b.6. 134

[42] ODNB

[43] The Murder Act of 1752 allowed the dissection of hanged murderers to be used for anatomical research.

[44] CCA D&C i.b.6, 135 & 148. The organist’s house had to be demolished to allow the construction of the Anatomy School. The college mason and carpenter were ordered to erect ‘a proper convenience’ in compensation.

[45] CCA Maps ChCh 13